Fertility

“Fertility benefits are the way to go, but European companies are not entirely convinced”

Employer fertility benefits have seen a dramatic rise in the US, but Europeans have not jumped on the trend

From Spotify and Facebook to Starbucks and Clif Bar, a growing number of US companies have introduced family-building benefits. Now, it’s time for Europe to support aspiring parents, says Jenny Saft.

When Jenny Saft decided to freeze her eggs aged 32, she was unaware of the many barriers women face regarding a relatively new procedure that was declared “no longer experimental” by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in 2012.

“After I spoke to my gynaecologist, I started to do a lot of research and I became really frustrated with the lack of transparency and stigma around this topic,” she says.

“It almost felt like doctors didn’t know how to have a proper conversation about this.”

Egg freezing retrievals increased dramatically from pre-pandemic levels with UK enquiries rising by as much as 50 per cent in the summer of 2020, compared to the prior year.

But although plans to extend the storage limit from 10 to 55 years are a welcome step in enabling women to freeze their eggs when they are younger, cost remains a major barrier to the treatment.

With the average total cost of egg freezing sometimes reaching more than £6,000 and additional yearly costs for storing the eggs, many aspiring mums like Saft are left disheartened.

“Most of these procedures, including IVF, are self-pay treatments. And even if the public healthcare funds partially cover them, it’s in very discriminating conditions,” she explains.

In her native Germany, the national policy reimburses 50 per cent of IVF/ICSI costs for up to three cycles but only for heterosexual couples in which women must be under the age of 40.

In England, whether you are able to access NHS fertility treatment depends on your GP’s postcode, with different regions offering different levels of access to NHS IVF and some offering none at all.

Women can be eligible for three rounds of NHS-funded IVF treatment if they have been trying unsuccessfully to start a family for two or more years, or if they have had 12 or more unsuccessful rounds of artificial insemination.

Unsurprisingly, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority found that the NHS funded only 35 per cent of IVF cycles in England in 2017 – the lowest level ever recorded by Britain’s fertility regulator – forcing many couples to go private or give up on treatment altogether.

This is due to a “scattered” system across Europe, says Saft. “We have to deal with a framework that doesn’t make sense and is not inclusive.

“If we look at the US where the concept of fertility benefits is exploding, we can see that more can be done for these couples.”

Although European healthcare systems are run at individual national levels, they are generally universal, unlike in the US where most citizens are covered by a combination of private insurance and various federal and state programmes.

However, Saft believes we can use this complexity to our advantage. Alongside her co-founder, Tobias Kaufhold, she brought the concept of fertility benefits closer to home by launching Apryl – a tech platform providing fertility benefits and working with employers across Europe.

“One of the biggest healthcare crises of our generation is infertility. Unfortunately, many people are still unaware of it,” she says.

“We started this journey because we realised that if you can’t afford treatment, you won’t be able to access fertility care.

“But if employers can implement strategic benefits, to give people access [to fertility care] they can make a huge statement not just by encouraging a more inclusive approach but by helping employees to plan their families and thrive in their career.”

Although Apryl is still an early-stage start-up, it aims to become the go-to benefits provider for progressive European companies, by offering employees fertility and family planning benefits, including consultations, access to clinics, as well as egg freezing, IVF and adoption.

“We want to be there for anyone in need of support regardless of sexual orientation or status,” says Saft.

“Diversity was something very clear for us from the very beginning and we knew that if we wanted to build this, we had to be something for everyone.”

Destigmatising fertility issues is another topic Saft is passionate about, as numerous studies have shown the major brunt of infertility is disproportionately borne by women.

“An increasing number of women choose to have kids later in their life and I think it’s important to speak openly about things like egg freezing or IVF.

“It’s funny that companies in Europe are still not entirely convinced that fertility benefits are the way to go. But part of the reason why they see this as niche is due to the stigma around fertility.”

Despite a lack of knowledge and a male-dominated VC space, she remains optimistic.

“I think the beauty is that we can develop solutions that can help employers and governments to work together and give more people access to care,” she says.

“In the US such benefits have come naturally because of their healthcare system. In Europe, they come more from a diversity inclusion angle, but I think we will see more companies implementing them soon.

“I also think governments will improve their set-ups and dedicate higher funds to this topic, in the long term.

“The best thing is that we have a business that people believe in and that can actually make a difference in the world.”

Diagnosis

Scientists turn human skin cells into eggs in IVF breakthrough

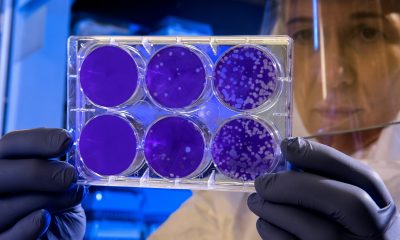

Researchers have created human eggs from skin cells, in a breakthrough that could transform IVF treatment for couples who have no other options.

The work remains at an early stage, but if scientists can refine the process it could allow women who are infertile due to age, illness or medical treatment to have genetically related eggs.

The same technique could also be used to make eggs for same-sex male couples.

Prof Shoukhrat Mitalipov, who led the research at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, said: “The largest group of patients who might benefit would be women of advanced maternal age.

“Another group are those who have been through chemotherapy because that can affect their ability to have viable eggs.”

While women are expected to be the primary beneficiaries, the skin cells used to make eggs need not come from potential mothers.

“We used female skin cells in this study, but you could use skin cells from males as well,” Mitalipov told the Guardian.

“You could make eggs for men, and that way, of course, this would be applicable to same-sex couples.”

The work draws on cloning techniques pioneered in the 1990s at the Roslin Institute in Scotland.

A team led by the late Ian Wilmut used somatic cell nuclear transfer – a process that moves genetic material between cells – to create Dolly the sheep.

The procedure involved removing the nucleus (the cell’s control centre containing genetic information) from an adult sheep cell and placing it into a sheep egg that had had its own nucleus removed.

The resulting embryo was carried to term in a surrogate mother.

The Oregon team took a similar approach by collecting skin cells from women and removing the nucleus from each.

The nucleus, which contains 46 chromosomes carrying around 20,000 genes that make up the human genetic code, was placed into healthy donor eggs that had had their own nuclei removed.

The main challenge for scientists was that healthy human eggs normally contain only 23 chromosomes.

Another 23 come from sperm during fertilisation, producing the full set of 46 required for development into an embryo and eventually a baby.

Writing in Nature Communications, the Oregon team described how they tackled the problem of excess chromosomes.

After fertilising the eggs with sperm, they activated them using a compound called roscovitine.

This caused the eggs to move roughly half of their chromosomes into a structure called a polar body – a small cell formed during egg development – leaving the remaining chromosomes to pair with those from the sperm.

In a healthy fertilised human egg, 23 chromosomes from the mother pair with 23 from the father.

However, the Oregon team found that in their lab-created eggs, the chromosomes paired up at random. This led to embryos with the wrong number of chromosomes or incorrect pairings.

“These abnormal chromosome complements would not be expected to result in a healthy baby,” said Prof Paula Amato, a co-author of the study at Oregon.

The team is now working to refine the process.

Of the 82 eggs created, fewer than 10 per cent developed to the stage at which embryos are typically transferred during IVF.

None were cultured beyond six days, suggesting the process remains inefficient.

Mitalipov described the work as a “proof of concept” with more challenges ahead. Perfecting the method and proving its safety in patients could take another decade.

“I think it’s going to be harder than what we’ve done over the years thus far, but it’s not impossible,” he said.

Other scientists praised the breakthrough.

Prof Richard Anderson of the University of Edinburgh said: “Many women are unable to have a family because they have lost their eggs, which can occur for a range of reasons including after cancer treatment.

“The ability to generate new eggs would be a major advance.

“There will be very important safety concerns, but this study is a step toward helping many women have their own genetic children.”

News

NHS introduces new ovarian cancer screening for high-risk women

High-risk women can now delay ovary removal surgery through NHS screening, helping them preserve fertility and avoid early surgical menopause.

The ROCA test tracks women with BRCA gene mutations every four months, monitoring cancer risk markers instead of requiring immediate preventive surgery.

University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust has begun rolling out the programme, with plans for national expansion after approval from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations greatly increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Normally, BRCA genes repair damaged DNA, but when faulty they allow tumours to grow more easily.

Breast cancer screening with mammograms is long established, but until now there has been no equivalent for ovarian cancer. Women carrying BRCA mutations were typically advised to have their ovaries removed preventively – a step that ends fertility and triggers menopause immediately.

The ROCA test monitors changes in CA125, a blood protein that can indicate ovarian cancer when levels rise.

By testing every four months, women can keep track of their risk while delaying surgery if they wish.

Professor Adam Rosenthal, consultant gynaecologist at UCLH, said the test was designed as a damage-limitation option for women not ready for surgery.

A raised result means patients can reconsider surgery, while regular monitoring increases the chance of detecting cancer early, when outcomes are better.

Natasha Wray learned she carried the BRCA gene after breast cancer treatment at 36. She was advised to have her ovaries removed but refused.

She said: “I was 36 at the time, and I said, absolutely not. I’d just gone through seven rounds of chemo, extensive surgery, and had sort of a year and a half, two years of my life caught up in cancer treatment, and I just wanted to be left alone.

“And I also didn’t want to go through a surgical menopause in my mid-30s.

“I also very much wanted to be a mum, so I definitely wanted to hold on to any fertility that I did have.

She initially paid privately for the ROCA tests and admitted they brought anxiety.

But Rosenthal said the screening helps keep the decision about surgery at the forefront for patients.

At 41, Wray had a baby. Two years later, her test results showed raised CA125 levels, and she delayed before eventually choosing surgery.

“It wasn’t easy,” she said.

“But I do think it’s really important as well that women’s bodies aren’t just seen as baby making bodies and machines.

“I very much wanted to be a mother. That wasn’t my sole purpose for holding onto my ovaries.

“It was very personal and it actually had nothing to do with anybody else. It was very much me, how I felt in my body, what had already been felt like to me, taken from me.”

NICE has approved the ROCA test for BRCA carriers, with health officials highlighting its cost-effectiveness and aiming to make it available across England.

Pregnancy

Preconception BMI linked to fertility and miscarriage risks

Preconception BMI outside the healthy range is linked to longer time to pregnancy and higher miscarriage risk, new research has revealed.

The study followed 3,033 pregnancy or preconception episodes among couples in Rotterdam between August 2017 and July 2021, examining how body mass index (BMI) – weight relative to height – affects fertility.

Women had a median age of 31.6 years and men 33.4. BMI categories were underweight (under 18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9) and obese (30 or greater).

Fecundability – the chance of conceiving in one menstrual cycle – declined with each BMI unit for both sexes.

Women with obesity had a 28 per cent lower chance of conceiving than women of normal weight, while overweight women had a 12 per cent reduction.

Overweight and obese men had an 11 per cent reduction compared with normal-weight men.

The researchers wrote: “A better understanding of the separate and combined associations of BMI in women and men with fertility and miscarriage outcomes is needed to develop novel targeted population strategies to optimise BMI from the preconception period onward.”

Of the cases studied, 17.8 per cent of women were classed as subfertile, meaning conception took more than 12 months. In addition, 11.3 per cent of pregnancies ended in miscarriage, defined as loss before 22 weeks’ gestation.

Underweight women had nearly twice the risk of subfertility compared with normal-weight women.

Overweight women faced a 35 per cent higher risk, while women with obesity had a 67 per cent higher risk.

Miscarriage risks were also higher outside the healthy BMI range: overweight women had a 49 per cent higher risk and women with obesity a 44 per cent higher risk than normal-weight women.

The median time to pregnancy across all participants was 3.7 months. The study also recorded use of assisted reproductive technology, including in vitro fertilisation, among couples struggling to conceive.

The investigators concluded: “Optimising BMI from the preconception period onward in women and men might be an important strategy to improve fertility and pregnancy outcomes.”

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoMothers’, not fathers’, mental health directly linked to their children’s, study shows

Menopause5 days ago

Menopause5 days agoNew report exposes perimenopause as biggest blind spot in women’s health

Diagnosis8 hours ago

Diagnosis8 hours agoScientists turn human skin cells into eggs in IVF breakthrough

Opinion3 weeks ago

Opinion3 weeks agoThe Future of femtech: Rebuilding the investment landscape

Wellness1 day ago

Wellness1 day agoDaily pill could delay menopause ‘by years,’ study finds

Entrepreneur4 weeks ago

Entrepreneur4 weeks agoUCL spin-out raises £2.5m to improve infant health with breast milk microbiome

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoWeightWatchers debuts menopause programme with Queen Latifah

Cancer4 weeks ago

Cancer4 weeks agoRound up: FDA clearance for AI-powered embryo assessment tool

Pingback: Amazon to expand access to fertility and family-building benefits - FemTech World