Pregnancy

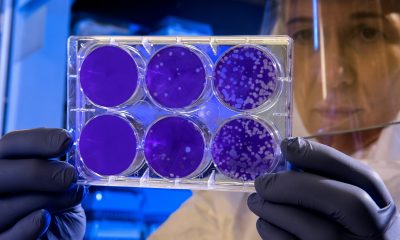

Does anaemia during pregnancy affect newborns’ risk of heart defects?

New research found that mothers who are anaemic in early pregnancy face a higher likelihood of giving birth to a child with a heart defect.

The study assessed the health records of 2,776 women from the United Kingdom Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD database with a child diagnosed with congenital heart disease who were matched to 13,880 women whose children did not have this condition.

Investigators found that 4.4 per cent of children with congenital heart disease and 2.8 per cent of children with normal heart function had anaemia.

After adjusting for potential influencing factors, the odds of giving birth to a child with congenital heart disease was 47 per cent higher among anaemic mothers.

The researchers concluded that: “The observed association between maternal anaemia in early pregnancy and increased risk of offspring CHD supports our recent evidence in mice. Approximately two-thirds of anaemia cases globally are due to iron deficiency. A clinical trial of periconceptional iron supplementation might be a minimally invasive and low-cost intervention for the prevention of some CHD if iron deficiency anaemia is proven to be a cause.”

“We already know that the risk of congenital heart disease can be raised by a variety of factors, but these results develop our understanding of anaemia specifically and take it from lab studies to the clinic. Knowing that early maternal anaemia is so damaging could be a game changer worldwide,” said corresponding author Duncan Sparrow, of the University of Oxford.

“Because iron deficiency is the root cause of many cases of anaemia, widespread iron supplementation for women – both when trying for a baby and when pregnant – could help prevent congenital heart disease in many newborns before it has developed.”

The study has been published in BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology.

-

Diagnosis4 weeks ago

Diagnosis4 weeks agoResearchers develop nasal therapeutic HPV vaccine

-

Fertility4 weeks ago

Fertility4 weeks agoWoman files lawsuit claiming fertility clinic ‘bootcamp’ caused her stroke

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoDoctors push back on ‘data-free’ ruling on menopause hormone therapy

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoInnovate UK relaunches £4.5m women founders programme

-

Menopause4 weeks ago

Menopause4 weeks agoSleep-related disorders linked to hypertension in postmenopausal women

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoSelf-guided hypnosis significantly reduces menopausal hot flushes, study finds

-

Insight1 week ago

Insight1 week agoFemtech in 2025: A year of acceleration, and what data signals for 2026

-

Opinion2 weeks ago

Opinion2 weeks agoWhy women’s health tech is crucial in bridging the gender health gap